Moving Beyond Email - Alternative Vehicles for Social Engineering

Executive Summary

[1]In 2022, cybercriminals used social engineering techniques in 20% of all data breaches. In 2021, Americans filed more than 550,000 complaints with the FBI regarding these types of crimes, resulting in reported losses exceeding $6.9 billion.

Social engineering is a cyber attack strategy threat actors use to manipulate users into disclosing sensitive information (social security numbers, bank account details, credit card details, etc.). It can also be used to carry out an attack that could compromise the user’s security. Social engineering often exploits human vulnerabilities, such as ignorance, greed, or fear.

The most common social engineering attacks happen via email phishing campaigns. The campaigns leverage social engineering tactics to manipulate a target into opening a malicious attachment or clicking on a harmful link. The goal is to infect the target's device with malware, which can then be used to steal sensitive information.

Although email remains a common vehicle for social engineering attacks, threat actors have been utilizing other means to manipulate their targets. Software repositories, social media platforms, ad injection, malvertising, and vishing have been used to persuade individuals into taking actions that benefit the attackers. Let’s investigate four social engineering methods that go beyond email phishing campaigns.

[1] The 12 Latest Types of Social Engineering Attacks (2023) | Aura

software repositories - pypi

Python Package Index (PyPI) is a repository that hosts software packages developed by the Python community. It serves as a central location for Python developers to publish and share their code with others, as well as discover and download packages developed by others.

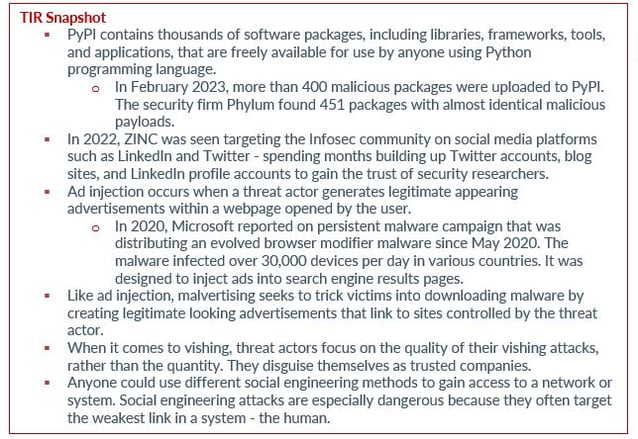

PyPI contains thousands of software packages, including libraries, frameworks, tools, and applications, that are freely available for use by anyone using Python programming language. The PyPI repository is maintained by volunteers who ensure that packages are hosted securely and meet certain quality standards.

In February 2023, more than 400 malicious packages were uploaded to PyPI. The security firm Phylum found 451 packages with almost identical malicious payloads. They were uploaded quickly and all at once. When the packages were installed, they created a malicious JavaScript extension that loaded every time a browser was opened – giving the malware persistence over reboots.

Unfortunately, this was not the first-time threat actors uploaded malicious software packages to PyPI. In January 2023, a threat actor by the name of Lolip0p uploaded three malicious packages to the repository. The packages were designed to drop malware on compromised developer systems. The packages were called colorslib (versions 4.6.11 and 4.6.12), httpslib (versions 4.6.9 and 4.6.11), and libhttps (version 4.6.12). The packages were downloaded more than 550 times before PyPI was able to remove them. These malicious packages specifically target software developers and show no signs of stopping.

sOCIAL MEDIA - lINKEDIN, FACEBOOK, ETC.

In November 2022, Avertium’s Cyber Threat Intelligence team published a Threat Intelligence Report featuring the North Korean threat actor, ZINC (a sub group of Lazarus). At the time, the threat actor was attacking organizations and individuals via highly sophisticated and evolving malware. They are best known for their 2014 retaliation attack against Sony Pictures Entertainment for the controversial film “The Interview”.

However, in 2022, ZINC was seen targeting the Infosec community on social media platforms such as LinkedIn and Twitter. The threat actor spent months building up Twitter accounts, blog sites, and LinkedIn profile accounts to gain the trust of security researchers. Once they built up their reputation on those platforms, they approached their targets and started conversations.

Their goal was to move their targets to other platforms such as Discord or WhatsApp or send them files using encrypted/PGP protected ZIPs. WhatsApp acted as a vehicle to deliver malicious payloads. Apart from using WhatsApp, ZINC also weaponized a variety of open-source software such as KiTTY, PuTTY, TightVNC, Sumatatra PDF Reader, and muPDF/Subliminal Recording software installer for their attacks.

advertising (ad) injection

Ad injection occurs when a threat actor generates legitimate appearing advertisements within a webpage opened by the user. When a user clicks on an ad, they are redirected to a site controlled by the threat actor. Ad injections can originate from various sources, including browser extensions, malware, and ad networks.

The browser extensions and ad injections are essentially plugins that users unintentionally download and run on their browsers. Compatible browsers include Chrome, Safari, and Firefox. Many ad injecting browser extensions are free because their developers aim to monetize ads by inserting unwanted malware. Ad injection also includes displaying fraudulent ads to website visitors on websites where ads are not typically shown. Superimposing ads on legitimate ads or placing ads in front of content is a form of malware, with the intent to steal clicks and revenue.

Keep in mind that most users click on ads because it is of interest to them – like an ad with a cheaper price for a product they would like to purchase. Threat actors can use this to their advantage by placing socially engineered malicious ads in front of content that they know their target wants to see – a growing threat for e-commerce businesses.

In December 2020, Microsoft reported on persistent malware campaign that was distributing an evolved browser modifier malware since May 2020. At its peak (in August 2020), the malware infected over 30,000 devices per day in various countries. The malware was designed to inject ads into search engine results pages. It also impacted several browsers including Google Chrome, Yandex, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox. Microsoft called the browser modifiers Adrozek.

Adrozek modifies a specific DLL for each targeted browser and installs browser extensions to insert unauthorized ads into web pages. If undetected and unblocked, these ads appear on top of legitimate ads from search engines, and users searching for certain keywords may unknowingly click on them. The attackers' goal is to earn revenue through affiliate advertising programs that pay based on the amount of traffic referred to sponsored affiliated pages.

malvertising

Like ad injection, malvertising seeks to trick victims into downloading malware by creating legitimate-looking advertisements that link to sites controlled by the threat actor. This approach is not new and has been a problem for more than a decade[1]. One method is to create malicious banner ads posted on participating websites, which may include malicious code to exploit browser vulnerabilities or link to a malicious website.

A slightly more recent approach is for threat actors to use Google Ads displayed in Google search results to link to malicious download sites. The paid ads are targeted towards searches for software or software updates, so users are looking to download executables. If a victim follows the ad link, they are directed to a phishing website that tricks them into downloading malware.

There has been a significant increase in malvertising via Google Ads since the start of 2023[2]. According to a Spamhaus report, AuroraStealer, IcedID, Meta Stealer, RedLine Stealer, and Vidar are being delivered to victims' machines through bad actors impersonating brands such as Adobe Reader, Gimp, Microsoft Teams, OBS, Slack, and Thunderbird using Google Ads.

[1] https://www.wired.com/2010/12/doubleclick/

[2] https://www.spamhaus.com/resource-center/a-surge-of-malvertising-across-google-ads-is-distributing-dangerous-malware/

vishing

Vishing is a cybercrime that most don’t relate to the cyber world because it involves stealing information via telephone. Most of the time, an attacker will call a target or leave a voicemail with a message of urgency, such as an emergency message from a prominent figure or a hefty fine for unpaid taxes. The success of a vishing attack depends on effective social engineering.

Today, threat actors are focusing on the quality of their vishing attacks, rather than the quantity. They even go as far as disguising themselves as trusted companies – a sneaky strategy called Enterprise Spoofing. Most people are aware of vishing calls and will ignore them, but what would you do if you received a call on your cell phone and the caller ID stated that the call was from your bank? You would likely answer it.

In February 2023, Coinbase stopped a cyberattack that was leveraging smishing and vishing. The threat actors attempted to trick Coinbase employees into sharing their login credentials and installing remote desktop applications. The employees received an “emergency” text message saying they needed to log into the company systems via a link to receive an important message.

One employee entered their credentials into a phishing page and the threat actors attempted to access Coinbase’s systems. However, the threat actors didn’t have the second authentication factor, so they were unsuccessful. After that didn’t work, the threat actors tried to get the employee on the phone by impersonating Coinbase’s IT staff. Their goal was to convince the employee to log into their workstation and install software that would allow the threat actor to access the system without needing credentials. Coinbase’s security team was able to thwart the attack before the employee was vished, but other organizations have not been as fortunate.

motive

PyPI - While there could be several reasons why a threat actor would upload malicious software packages to an open-source software repository, there are two main reasons why we think most attackers may be doing so - to launch a supply chain attack and to exploit a trusted platform. A supply chain attack would be easy to accomplish due to PyPI being a widely used platform. By compromising a trusted platform, threat actors can gain access to systems that rely on a particular package.

Social Media - ZINC’s activity is a reminder that even professional social media platforms like LinkedIn can entice cybercriminals to conduct malicious activity. Social media is an excellent place for threat actors to not only build and establish credibility, but to widen their pool of targets. They wouldn’t have been able to easily find as many researchers through other me

Ad Injection and Malvertising - The reasons why threat actors would want to socially engineer ads are simple – to seek financial gain and to obtain sensitive information. By inserting their own ads into legitimate websites, attackers can earn money for every click or impression generated by unsuspecting users. They can also trick people into revealing sensitive information.

Vishing - Like ad injection and malvertising, threat actors who utilize vishing are looking for a big pay day. They also may resort to vishing to be more targeted in their attacks. By gathering information about the employee (name, title, credentials, etc.), an attacker can further their attacks against an organization (large corporations, government entities, research centers, etc.).

defense

Anyone could use different social engineering methods to gain access to a network or system. Social engineering attacks are especially dangerous because they often target the weakest link in a system - the human. Unlike software vulnerabilities, which can be patched, human vulnerabilities are a lot more difficult to address.

One of the primary reasons why social engineering attacks are so dangerous is because they can be difficult to detect due to the human component of the attack. However, there are ways your organization can remain safe:

- Software Repositories

- There is a growing threat regarding supply chain attacks. One of the ways threat actors can trick developers into downloading malicious packages is via typosquatting. When it comes to software repositories, the typosquatting mimics popular packages such as pandas or bitcoinlib. By verifying that the name of the package is spelled correctly, developers can avoid becoming a victim.

- There is a growing threat regarding supply chain attacks. One of the ways threat actors can trick developers into downloading malicious packages is via typosquatting. When it comes to software repositories, the typosquatting mimics popular packages such as pandas or bitcoinlib. By verifying that the name of the package is spelled correctly, developers can avoid becoming a victim.

- Social Media

- Social media social engineering attacks can be thwarted if users avoid clicking on links and opening attachments from new connections. They could be sending you malicious attachments and links to infect your device with malware.

- Privacy settings should be adjusted to ensure that personal information is not public.

- Avoid sharing your work email address and job role (although this may be impossible on social media platforms like LinkedIn).

- Avoid sharing phone numbers.

- Avoid sharing your financial status.\

- Ad Injection & Malvertising

- Organizations should use ad blockers to help block ads to improve the user’s browsing experience.

- Keep all browser and anti-virus software up to date.

- Users should be cautious of promotions and offers that require software installation or browser extensions. This could be a front for an ad injection attack.

- Use VPNs, as they can encrypt internet traffic and protect against ad injection attacks that occur on unsecured internet connections.

- Vishing

- If a caller has a sense of urgency and wants you to act immediately, take a moment to verify the caller. Threat actors are hoping that victims aren’t thinking too hard.

- If the caller claims to represent someone of importance, hang up and call the individual back with the number you already have for that person.

- Be suspicious of anyone claiming to need your personal information over the phone.

- MFA can help prevent vishing attacks and can make it difficult for attackers to gain access to sensitive information.

- Organizations can use call screening that requires callers to authenticate themselves. They can also use voice recognition to help thwart a vishing attack.

how avertium is protecting our customers

It’s important to get ahead of the curve by being proactive with protecting yourself and your organization, instead of waiting to put out a massive fire. Avertium offers the following services to keep you and your organization safe:

- Expanding endpoints, cloud computing environments, and accelerated digital transformation have decimated the perimeter in an ever-expanding attack surface. Avertium’s offers Attack Surface Management, so you’ll have no more blind spots, weak links, or fire drills.

- Fusion MXDR is the first MDR offering that fuse together all aspects of security operations into a living, breathing, threat-resistant XDR solution. By fusing insights from threat intelligence, security assessments, and vulnerability management into our MDR approach, Fusion MXDR offers a more informed, robust, and cost-effective approach to cybersecurity – one that is great than the sum of its parts.

- Avertium offers VMaaS to provide a deeper understanding and control over organizational information security risks. If your enterprise is facing challenges with the scope, resources, or skills required to implement a vulnerability management program with your team, outsourced solutions can help you bridge the gap.

- Avertium offers Zero Trust Architecture, like AppGate, to stop malware lateral movement.

- Avertium offers user awareness training through KnowBe4. The service also Incident Response Table-Top exercises (IR TTX) and Core Security Document development, as well as a comprehensive new-school approach that integrates baseline testing using mock attacks.

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION

Latest attack on PyPI users shows crooks are only getting better | Ars Technica

Researchers Uncover 3 PyPI Packages Spreading Malware to Developer Systems (thehackernews.com)

https://www.wired.com/2010/12/doubleclick/

What is Vishing and Is It A Threat to Your Business? - Security Boulevard

The 12 Latest Types of Social Engineering Attacks (2023) | Aura

Python Packages: Five Real Python Favorites – Real Python

PyPI · The Python Package Index

What can we learn from the latest Coinbase cyberattack? - Help Net Security

An In-Depth Look at the North Korean Threat Actor, ZINC (avertium.com)

What Is Ad Injection and How To Tackle It - Publir

The latest threat to digital advertising? 'Ad injections' | Marketing Dive

Over 4,500 WordPress Sites Hacked to Redirect Visitors to Sketchy Ad Pages (thehackernews.com)

APPENDIX II: Disclaimer

This document and its contents do not constitute, and are not a substitute for, legal advice. The outcome of a Security Risk Assessment should be utilized to ensure that diligent measures are taken to lower the risk of potential weaknesses be exploited to compromise data.

Although the Services and this report may provide data that Client can use in its compliance efforts, Client (not Avertium) is ultimately responsible for assessing and meeting Client's own compliance responsibilities. This report does not constitute a guarantee or assurance of Client's compliance with any law, regulation or standard.

COPYRIGHT: Copyright © Avertium, LLC and/or Avertium Tennessee, Inc. | All rights reserved.